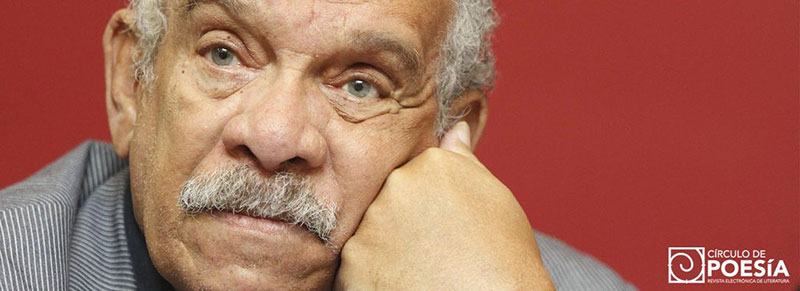

Ha muerto el poeta Derek Walcott (1930-2017). Presentamos, en versión de Antonio Resines y Herminia Bevia, un poema del Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1992. El poema está incluido en el volumen El testamento de Arkansas, publicado por Visor en 1994. Hay críticos que sostienen que Walcott es el mayor poeta de lengua inglesa de nuestro tiempo.

Ha muerto el poeta Derek Walcott (1930-2017). Presentamos, en versión de Antonio Resines y Herminia Bevia, un poema del Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1992. El poema está incluido en el volumen El testamento de Arkansas, publicado por Visor en 1994. Hay críticos que sostienen que Walcott es el mayor poeta de lengua inglesa de nuestro tiempo.

LA LUZ DEL MUNDO

Kaya ahora, necesito kaya ahora,

Necesito Kaya ahora,

Porque cae la lluvia.

—Bob Marley

Marley cantaba rock en el estéreo del autobús

y aquella belleza le hacía en voz baja los coros.

Yo veía dónde las luces realzaban, definían,

los planos de sus mejillas; si esto fuera un retrato

se dejarían los claroscuros para el final, esas luces

transformaban en seda su negra piel; yo habría añadido un pendiente,

algo sencillo, en otro bueno, por el contraste, pero ella

no llevaba joyas. Imaginé su aroma poderoso y

dulce, como el de una pantera en reposo,

y su cabeza era como mínimo un blasón.

Cuando me miró, apartando luego la mirada educadamente

porque mirar fijamente a los desconocidos no es de buen gusto,

era como una estatua, como un Delacroix negro

La Libertad guiando al pueblo, la suave curva

del blanco de sus ojos, la boca en caoba tallada,

su torso sólido, y femenino,

pero gradualmente hasta eso fue desapareciendo en el

atardecer, excepto la línea

de su perfil, y su mejilla realzada por la luz,

y pensé, ¡Oh belleza, eres la luz del mundo!

No fue la única vez que se me vino a la cabeza la frase

en el autobús de dieciséis asientos que traqueteaba entre

Gros-Islet y el Mercado, con su crujido de carbón

y la alfombra de basura vegetal tras las ventas del sábado,

y los ruidosos bares de ron, ante cuyas puertas de brillantes colores

se veían mujeres borrachas en las aceras, lo más triste del mundo,

recorriendo a tumbos su semana arriba, a tumbos su semana abajo.

El mercado, al cerrar aquella noche del Sábado,

me recordaba una infancia de errantes faroles

colgados de pértigas en las esquinas de las calles, y el viejo estruendo

de los vendedores y el tráfico, cuando el farolero trepaba,

enganchaba una lámpara en su poste y pasaba a otra,

y los niños volvían el rostro hacia su polilla, sus

ojos blancos como sus ropas de noche; el propio mercado

estaba encerrado en su oscuridad ensimismada

y las sombras peleaban por el pan en las tiendas,

o peleaban por el hábito de pelear

en los eléctricos bares de ron. Recuerdo las sombras.

El autobús se llenaba lentamente mientras oscurecía en la estación.

Yo estaba sentado en el asiento delantero, me sobraba tiempo.

Miré a dos muchachas, una con un corpiño

y pantalones cortos amarillos, una flor en el cabello,

y sentí una pacífica lujuria; la otra era menos interesante.

Aquel anochecer había recorrido las calles de la ciudad

donde había nacido y crecido, pensando en mi madre

con su pelo blanco teñido por la luz del atardecer,

y las inclinadas casas de madera que parecían perversas

en su retorcimiento; había fisgado salones

con celosías a medio cerrar, muebles a oscuras,

poltronas, una mesa central con flores de cera,

y la litografía del Sagrado Corazón,

buhoneros vendiendo aún a las calles vacías:

dulces, frutos secos, chocolates reblandecidos, pasteles de

nuez, caramelos.

Una anciana con un sombrero de paja sobre su pañuelo

se nos acercó cojeando con una cesta; en algún lugar,

a cierta distancia, había otra cesta más pesada

que no podía acarrear. Estaba aterrada.

Le dijo al conductor: «Pas quittez moi a terre»,

Qué significa, en su patois: «No me deje aquí tirada»,

Qué es, en su historia y en la de su pueblo:

«No me deje en la tierra» o, con un cambio de acento:

«No me deje la tierra» [como herencia];

«Pas quittez moi a terre, transporte celestial,

No me dejes en tierra, ya he tenido bastante».

El autobús se llenó en la oscuridad de pesadas sombras

que no deseaban quedarse en la tierra; no, que serían abandonadas

en la tierra y tendrían que buscarse la vida.

El abandono era algo a lo que se habían acostumbrado.

Y yo les había abandonado, lo supe allí,

sentado en el autobús, en la media luz tranquila como el mar,

con hombres inclinados sobre canoas, y las luces naranjas

de la punta de Vigie, negras barcas en el agua;

yo, que nunca pude dar consistencia a mi sombra

para convertirla en una de sus sombras, les había dejado su tierra,

sus peleas de ron blanco y sus sacos de carbón,

su odio a los capataces, a toda autoridad.

Me sentía profundamente enamorado de la mujer junto a la ventana.

Quería marcharme a casa con ella aquella noche.

Quería que ella tuviera la llave de nuestra cabaña

junto a la playa en GrosIlet; quería que se pusiese

un camisón liso y blanco que se vertiera como agua

sobre las negras rocas de sus pechos, yacer

simplemente a su lado junto al círculo de luz de un quinqué de latón

con mecha de queroseno, y decirle en silencio

que su cabello era como el bosque de una colina en la noche,

que un goteo de ríos recorría sus axilas,

que le compraría Benin si así lo deseaba,

y que jamás la dejaría en la tierra. Y decírselo también a los otros.

Porque me embargaba un gran amor capaz de hacerme

romper en llanto,

y una pena que irritaba mis ojos como una ortiga,

temía ponerme a sollozar de repente

en el transporte público con Marley sonando,

y un niño mirando sobre los hombros

del conductor y los míos hacia las luces que se aproximaban,

hacia el paso veloz de la carretera en la oscuridad del campo,

las luces en las casas de las pequeñas colinas,

y la espesura de estrellas; les había abandonado,

les había dejado en la tierra, les dejé para que cantaran

las canciones de Marley sobre una tristeza real como el olor

de la lluvia sobre el suelo seco, o el olor de la arena mojada,

y el autobús resultaba acogedor gracias a su amabilidad,

su cortesía, y sus educadas despedidas

a la luz de los faros. En el fragor,

en la música rítmica y plañidera, el exigente aroma

que procedía de sus cuerpos. Yo quería que el autobús

siquiera su camino para siempre, que nadie se bajara

y dijera buenas noches a la luz de los faros

y tomara el tortuoso camino hacia la puerta iluminada,

guiado por las luciérnagas; quería que la belleza de ella

penetrara en la calidez de la acogedora madera,

ante el aliviado repiquetear de platos esmaltados

en la cocina, y el árbol en el patio,

pero llegué a mi parada. Delante del Hotel Halcyon.

El vestíbulo estaría lleno de transeúntes como yo.

Luego pasearía con las olas playa arriba.

Me bajé del autobús sin decir buenas noches.

Ese buenas noches estaría lleno de amor inexpresable.

Siguieron adelante en su autobús, me dejaron en la tierra.

Entonces, un poco más allá, el vehículo se detuvo. Un hombre

gritó mi nombre desde la ventanilla.

Caminé hasta él. Me tendió algo.

Se me había caído del bolsillo una cajetilla de cigarrillos.

Me la devolvió. Me di la vuelta para ocultar mis lágrimas.

No deseaban nada, nada había que yo pudiera darles

salvo esta cosa que he llamado «La Luz del Mundo».

The Light of the World

Kaya now, got to have kaya now,

Got to have kaya now,

For the rain is falling.

—Bob Marley

Marley was rocking on the transport’s stereo

and the beauty was humming the choruses quietly.

I could see where the lights on the planes of her cheek

streaked and defined them; if this were a portrait

you’d leave the highlights for last, these lights

silkened her black skin; I’d have put in an earring,

something simple, in good gold, for contrast, but she

wore no jewelry. I imagined a powerful and sweet

odour coming from her, as from a still panther,

and the head was nothing else but heraldic.

When she looked at me, then away from me politely

because any staring at strangers is impolite,

it was like a statue, like a black Delacroix’s

Liberty Leading the People , the gently bulging

whites of her eyes, the carved ebony mouth,

the heft of the torso solid, and a woman’s,

but gradually even that was going in the dusk,

except the line of her profile, and the highlit cheek,

and I thought, O Beauty, you are the light of the world!

It was not the only time I would think of that phrase

in the sixteen-seater transport that hummed between

Gros-Islet and the Market, with its grit of charcoal

and the litter of vegetables after Saturday’s sales,

and the roaring rum shops, outside whose bright doors

you saw drunk women on pavements, the saddest of all things,

winding up their week, winding down their week.

The Market, as it closed on this Saturday night,

remembered a childhood of wandering gas lanterns

hung on poles at street corners, and the old roar

of vendors and traffic, when the lamplighter climbed,

hooked the lantern on its pole and moved on to another,

and the children turned their faces to its moth, their

eyes white as their nighties; the Market

itself was closed in its involved darkness

and the shadows quarrelled for bread in the shops,

or quarrelled for the formal custom of quarrelling

in the electric rum shops. I remember the shadows.

The van was slowly filling in the darkening depot.

I sat in the front seat, I had no need for time.

I looked at two girls, one in a yellow bodice

and yellow shorts, with a flower in her hair,

and lusted in peace, the other less interesting.

That evening I had walked the streets of the town

where I was born and grew up, thinking of my mother

with her white hair tinted by the dyeing dusk,

and the titling box houses that seemed perverse

in their cramp; I had peered into parlours

with half-closed jalousies, at the dim furniture,

Morris chairs, a centre table with wax flowers,

and the lithograph of Christ of the Sacred Heart ,

vendors still selling to the empty streets—

sweets, nuts, sodden chocolates, nut cakes, mints.

An old woman with a straw hat over her headkerchief

hobbled towards us with a basket; somewhere,

some distance off, was a heavier basket

that she couldn’t carry. She was in a panic.

She said to the driver: “Pas quittez moi à terre ,”

which is, in her patois: “Don’t leave me stranded,”

which is, in her history and that of her people:

“Don’t leave me on earth,” or, by a shift of stress:

“Don’t leave me the earth” [for an inheritance];

“Pas quittez moi à terre , Heavenly transport,

Don’t leave me on earth, I’ve had enough of it.”

The bus filled in the dark with heavy shadows

that would not be left on earth; no, that would be left

on the earth, and would have to make out.

Abandonment was something they had grown used to.

And I had abandoned them, I knew that there

sitting in the transport, in the sea-quiet dusk,

with men hunched in canoes, and the orange lights

from the Vigie headland, black boats on the water;

I, who could never solidify my shadow

to be one of their shadows, had left them their earth,

their white rum quarrels, and their coal bags,

their hatred of corporals, of all authority.

I was deeply in love with the woman by the window.

I wanted to be going home with her this evening.

I wanted her to have the key to our small house

by the beach at Gros-Ilet; I wanted her to change

into a smooth white nightie that would pour like water

over the black rocks of her breasts, to lie

simply beside her by the ring of a brass lamp

with a kerosene wick, and tell her in silence

that her hair was like a hill forest at night,

that a trickle of rivers was in her armpits,

that I would buy her Benin if she wanted it,

and never leave her on earth. But the others, too.

Because I felt a great love that could bring me to tears,

and a pity that prickled my eyes like a nettle,

I was afraid I might suddenly start sobbing

on the public transport with the Marley going,

and a small boy peering over the shoulders

of the driver and me at the lights coming,

at the rush of the road in the country darkness,

with lamps in the houses on the small hills,

and thickets of stars; I had abandoned them,

I had left them on earth, I left them to sing

Marley’s songs of a sadness as real as the smell

of rain on dry earth, or the smell of damp sand,

and the bus felt warm with their neighbourliness,

their consideration, and the polite partings

in the light of its headlamps. In the blare,

in the thud-sobbing music, the claiming scent

that came from their bodies. I wanted the transport

to continue forever, for no one to descend

and say a good night in the beams of the lamps

and take the crooked path up to the lit door,

guided by fireflies; I wanted her beauty

to come into the warmth of considerate wood,

to the relieved rattling of enamel plates

in the kitchen, and the tree in the yard,

but I came to my stop. Outside the Halcyon Hotel.

The lounge would be full of transients like myself.

Then I would walk with the surf up the beach.

I got off the van without saying good night.

Good night would be full of inexpressible love.

They went on in their transport, they left me on earth.

Then, a few yards ahead, the van stopped. A man

shouted my name from the transport window.

I walked up towards him. He held out something.

A pack of cigarettes had dropped from the pocket.

He gave it to me. I turned, hiding my tears.

There was nothing they wanted, nothing I could give them

but this thing I have called “The Light of the World.

En www.circulodepoesia.com

Me gustó el relato detrás de lo leído invitando al lector a ser parte del mismo por parte de la…