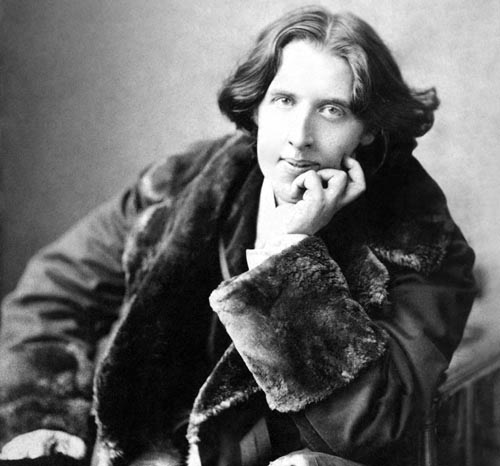

Por Oscar Wilde

I.

Ya no vestía su casaca escarlata,

Porque rojos son la sangre y el vino

Y sangre y vino había en sus manos

Cuando lo sorprendieron con la muerta,

La pobre muerta a la que había amado

Y a la que asesinó en su lecho.

Entre los reos caminaba

Con un mísero uniforme gris

Y una gorrilla en la cabeza;

Parecía andar ligero y alegre,

Pero nunca vi a un hombre que mirara

Con tanta avidez la luz del día.

Nunca vi a un hombre que mirara

Con ojos tan ávidos

Ese pequeño toldo azul

Al que los presos llaman cielo

Y cada nube que pasaba

Con sus velas de plata.

Yo, con otras almas en pena,

Caminaba en otro corro

Y me preguntaba si aquel hombre habría hecho

Algo grande o algo pequeño,

Cuando una voz susurró a mis espaldas:

«¡A ese tipo lo van a colgar!»

¡Santo Cristo! Hasta los muros de la cárcel

de pronto parecieron vacilar

y el cielo sobre mi cabeza se convirtió

en un casco de acero ardiente;

y, aunque yo también era un alma en pena,

mi pena no podía sentirla.

Sólo sabía que una idea obsesiva

Apresuraba su paso, y por qué

Miraba al día deslumbrante

Con tan ávidos ojos;

Aquel hombre había matado lo que amaba,

Y por eso iba a morir.

Aunque todos los hombres matan lo que aman,

Que lo oiga todo el mundo,

Unos lo hacen con una mirada amarga,

Otros con una palabra zalamera;

El cobarde con un beso,

¡El valiente con una espada!.

Unos matan su amor cuando son jóvenes,

Y otros cuando son viejos;

Unos lo ahogan con manos de lujuria,

Otros con manos de oro;

El más piadoso usa un cuchillo,

Pues así el muerto se enfría antes.

Unos aman muy poco, otros demasiado,

Algunos venden y otros compran;

Unos dan muerte con muchas lágrimas

Y otros sin un suspiro:

Pero aunque todos los hombres matan lo que aman,

No todos deben morir por ello.

No todo hombre muere de muerte infamante

En un día de negra vergüenza,

Ni le echan un dogal al cuello,

Ni una mortaja sobre el rostro,

Ni cae con los pies por delante,

A través del suelo, en el vacío.

No todo hombre convive con hombres callados

Que lo vigilan noche y día,

Que lo vigilan cuando intenta llorar

Y cuando intenta rezar,

Que lo vigilan por miedo a que él mismo robe

Su presa a la prisión.

No todo hombre despierta al alba y ve

Aterradoras figuras en su celda,

Al trémulo capellán con ornamentos blancos,

Y al director, de negro brillante,

Con el rostro amarillo de la sentencia.

No todo hombre se levanta con lastimera prisa

Para vestir sus ropas de condenado

Mientras algún doctor de zafia lengua disfruta

Y anota cada nueva crispación nerviosa,

Manoseando un reloj cuyo débil tic-tac

Suena lo mismo que horribles martillazos.

No todo hombre siente esa asquerosa sed

Que le reseca a uno la garganta antes

De que el verdugo, con sus guantes de faena,

Franquee la puerta acolchada

y le ate con tres correas de cuero

Para que la garganta no vuelva a sentir sed.

No todo hombre inclina la cabeza

Para escuchar el oficio de difuntos

Ni, mientras la angustia de su alma

Le dice que no está muerto,

Pasa junto a su propio ataúd

Camino del atroz tinglado.

No todo hombre mira hacia lo alto

A través de un tejadillo de cristal,

Ni reza con labios de barro

Para que cese su agonía

Ni siente en su mejilla estremecida

El beso de Caifás.

II.

Durante seis semanas el guardia de corps recorrió el patio

con su mísero uniforme gris;

llevaba en la cabeza su gorrilla

y parecía andar ligero y alegre,

pero nunca vi a un hombre que mirara

con tanta avidez la luz del día.

Nunca vi a un hombre que mirara

con ojos tan ávidos

ese pequeño toldo azul

al que los presos llaman cielo,

y cada nube vagabunda que arrastrada

sus enmarañados vellones.

No retorcía sus manos, como hacen

esos insensatos que pretenden

criar a la raptada esperanza

en la cueva de la negra desesperación;

él solo miraba hacia el sol

y bebía el aire matinal.

No retorcía sus manos ni lloraba,

ni miraba de refilón, ni languidecía,

sino que bebía el aire como si creyera

que contenía algún calmante saludable;

¡bebía el sol a bocanadas

como si creyera que era vino!

Y yo y todas las almas en pena

que andábamos en el otro corro

olvidábamos si había hecho

algo grande o algo pequeño

y observábamos con triste mirada de asombro

al hombre que iban a colgar.

Pues era extraño verlo cruzar

con un paso tan ágil y alegre,

y era extraño verlo mirar

con tanta avidez la luz del día,

y era extraño pensar que él

tuviera deuda por pagar.

Pues el roble y el olmo tienen hojas amables

que brotan en la primavera,

pero es macabro de ver el árbol de la horca

con su raíz mordida por la víbora

y, verde o seco, un hombre ha de morir

para que ese árbol dé su fruto.

Lo más elevado es esa sede de gracia

hacia la que tiende todo lo terrenal,

pero ¿quién querría estar con corbata de cáñamo

en lo alto de un patíbulo

y a través de un dogal de asesino

echar su última mirada al cielo?

Dulce es bailar al son de los violines

cuando el amor y la vida son hermosos;

bailar al son de flautas y laúdes

es delicado y exquisito,

¡pero no es agradable bailar en el aire

con ágiles pies!

Así, con ojos curiosos y enloquecedoras conjeturas

lo observábamos día tras día

y cada uno de nosotros se preguntaba

si no acabaría de la misma manera,

pues nadie puede decir en qué rojo infierno puede extraviarse su alma ciega.

Por fin el muerto dejó de pasear

entre los reos

y comprendí que estaba en la terrible

celda del banquillo negro

y que nunca volvería a ver su rostro

ni para bien ni para mal.

Como los barcos condenados que se cruzan

en la tempestad, nuestros caminos se cruzaron,

pero ni hicimos señales, ni dijimos palabras,

nada teníamos que decir;

pues no fue nuestro encuentro en la noche sagrada,

sino el día ignominioso.

A ambos nos rodeaba el muro de una cárcel

los dos éramos proscritos;

el mundo nos había arrojado de su seno

y Dios de su providencia,

y el cepo de hierro que acecha el pecado

nos había hecho caer en su trampa.

III.

En el patio de los deudores las piedras son duras

y el rezumante muro es alto,

y allí era donde él tomaba el aire

bajo el cielo plomizo,

y a cada lado caminaba un guardián

por miedo a que aquel hombre muriese.

O, si no, se sentaba con quienes vigilaban

su angustia noche y día;

con quienes le vigilaban al levantarse a llorar

y recogerse para rezar;

con quienes le vigilaban por temor a que él mismo

robara su presa al patíbulo.

El director explicaba

el reglamento rigurosamente

el doctor decía que la muerte

era sólo un hecho científico;

y dos veces al día le visitaba el capellán

y le dejaba un folleto.

Y dos veces al día se fumaba una pipa

y se bebía una jarra de cerveza;

su alma estaba resuelta y no tenía

resquicios para el miedo;

solía decir que le alegraba

que el día del verdugo estuviera próximo.

Pero por qué decía algo tan raro

ningún guardián osaba preguntarle:

pues a quien un destino de guardián

les es dado por tarea,

debe poner un cerrojo en sus labios

y convertir su rostro en una máscara.

Porque, si no, podría conmoverse y tratar

de confortar y consolar,

y ¿qué haría la piedad humana

encerrada en el cubil del asesino?

¿Qué palabra de gracia en tal lugar

podría socorrer el alma de un hermano?

Cabizbajos y vacilantes en torno al patio

desfilábamos en el cortejo de los locos.

No nos importaba: sabíamos que éramos

la brigada del mismísimo diablo,

y cráneos rapados y pies de plomo

componían una alegre mascarada.

Sacábamos hebras de sogas embreas

con dedos embotados y sangrantes;

frotábamos puertas y fregábamos suelos,

y limpiábamos los barrotes relucientes;

y, fila a fila, enjabonábamos las tablas,

y hacíamos ruido con los cubos.

Cosíamos sacos, partíamos piedras,

hacíamos girar el polvoriento taladro,

chocábamos los platos y gritábamos himnos

y sudábamos en el molino,

pero en el corazón de cada uno

se agazapaba el terror.

Tan agazapado, que cada día

pasaba como una ola cargada de algas

y olvidábamos la amarga suerte

que espera al tonto y al bribón,

hasta que , una vez, al volver del trabajo,

pasamos junto a una fosa abierta.

Con su bostezo el pardo agujero reclamaba algo vivo;

el propio barro pedía sangre

al sediento patio de asfalto,

y supimos que, antes de la belleza de otro amanecer

un preso sería colgado.

Entramos derechos, con el alma absorta

en muerte, terror y destino;

el verdugo con su maletín

pasó por lo oscuro arrastrando los pies

y yo temblé tanteando el camino

hacia mi tumba numerada.

Aquella noche las desiertas galerías

estaban pobladas por formas de espanto

y, de arriba a abajo de la ciudad de hierro,

no se oía ni un paso furtivo

y, a través de los barrotes que ocultan las estrellas,

parecían atisbar rostros blancos.

Él descansaba como quien yace y sueña

en un gustoso prado;

los guardianes le guardaban mientras dormía

y no comprendían

cómo podía alguien dormir tan dulce sueño

con verdugo tan a mano.

Pero no hay sueño cuando tienen que llorar

y así nosotros –el tonto, el farsante , el bribón-

hicimos aquella interminable vigilia

y por cada cerebro, en manos del dolor,

reptaba el terror de otro.

¡Ay, es algo terrible

sentir la culpa ajena!

porque recta, a fondo, la espada del pecado

se hundió hasta su envenenada empuñadura,

y cual plomo candente fueron las lágrimas que vertimos

por la sangre que no habíamos derramado.

Los guardianes con calzados de fieltro

se acercaban a las puertas atrancadas

y se asomaban y veían con ojos de pasmo

figuras grises en el suelo,

y se preguntaban por qué se postraban a rezar

hombre que nunca antes rezaron.

Toda la noche rezamos postrados,

¡locos plañideros de un cadáver!

Las agitadas plumas de la medianoche

sacudían los penachos del coche fúnebre

ya vino agrio en una esponja

sabía el remordimiento.

Cantó el gallo gris, cantó el gallo rojo,

pero el día nunca llegaba

y contrahechas formas del terror se agazapaban

en los rincones donde yacíamos;

y los espíritus malignos que deambulan de noche

parecían actuar ante nosotros..

Pasaban deslizándose, pasaban deprisa,

como viajeros por la niebla;

se burlaban de la luna en un rigodón

de delicado giro y meneo,

y con solemne paso y repulsiva gracia

acudían a visiones a la cita.

Haciendo muecas los veíamos pasar,

tenues sombras cogidas de la mano,

arriba, abajo, en una fuga fantasmal

bailaban una zarabanda

¡y los malditos grotescos trazaban arabescos

como el viento sobre arena!

Con piruetas de marionetas

bailaban de puntillas,

mas con flautas de miedo llenaban los oídos

conduciendo su horrible mascarada

y cantaban para despertar al muerto.

“¡Yubu!”, gritaban, “ancho es el mundo,

pero los pies con grilletes cojean,

y echar los dados una o dos veces

es un juego de caballeros,

mas nunca gana quien juega con el pecado

en la secreta casa de la vergüenza.”

No eran seres de aire aquellos saltimbanquis

que brincaban con tanto gozo;

para aquellos cuyas vidas estaban encadenadas

y cuyos pies no podían andar libremente

¡ah, llagas de Cristo! eran cosas vivas

y terribles de ver.

En corro, en corro, valsaban y giraban

unos dando vueltas en parejas sonrientes;

con el paso menudo de una mujer equívoca

subía otro las escaleras,

y con sutil sarcasmo y mirada halagüeña

nos ayudaban en nuestras plegarias.

El viento matinal empezó a gemir,

pero la noche persistía;

en su rueca gigante, el velo de las sombras

se corrió hasta que cada hebra estuvo devanada

y, mientras rezábamos, crecía nuestro miedo

a la justicia del sol.

El viento gimiente rondó peregrino

en torno al lloroso muro de la cárcel

hasta que, como una rueda giratoria de acero,

oímos arrastrarse a los minutos.

¡Oh viento gimiente! ¿qué hemos hecho

para tener tal senescal?

Por fin vi los barrotes hechos sombra,

como celosía forjada en plomo,

moverse por la pared encalada

frente a mi lecho de tres tablas

y supe que en algún sitio en el mundo el alba terrible de Dios era roja.

A las seis en punto limpiamos las celdas,

a las siete, todo quedó en silencio,

pero el susurro y el batir de una ala inmensa

parecían llenar la cárcel,

pues el señor de la muerte con helado aliento

había entrado para matar.

No pasó entre pompas de púrpura

Ni cabalgando un corcel de blanca luna.

Tres metros de soga y una tabla de corredera

era cuanto necesitaba la horca,

así que el heraldo con traje de vergüenza

llegó a realizar su acción secreta.

Éramos como hombres que por un pantano

de inmunda oscuridad avanzan tanteando;

no nos atrevíamos a susurrar una oración ni a dar suelta a nuestra angustia;

algo había muerto en cada uno de nosotros

y lo que había muerto era la esperanza

Porque la feroz justicia del hombre

sigue su curso y no admite desvíos;

da muerte al débil, da muerte al fuerte,

tiene un paso mortal :

¡Con talón de hierro mata al fuerte,

la monstruosa parricida!

Esperamos el toque de las ocho

-todas las lenguas resecas por la sed-

Pues el toque de las ocho es el toque del destino

que convierte en maldito a un hombre

y el destino emplea un nudo corredizo

para el mejor de los hombres y para el peor.

No teníamos otra cosa que hacer

sino esperar la señal que había de llegar;

por eso, como piedras en un valle solitario,

seguíamos sentados inmóviles y silenciosos,

¡pero los corazones de todos latían graves y rápidos

Como un loco golpeando un tambor!

Con repentina conmoción el reloj de la cárcel

batió el aire trémulo

y de toda la prisión se elevó un gemido

de impotente desesperación,

como el grito que alarmados cortejos oyen

de algún leproso en su cubil.

E igual que las cosas más terribles

en el cristal de un sueño

vimos la ensebada soga de cáñamo

colgando de la negruzca viga

y escuchamos la oración que el dogal del verdugo

estranguló en un gemido.

Y todo el dolor que impulsó

a dar aquel grito tan amargo,

y los feroces remordimientos y los sudores de sangre,

nadie los comprendió mejor que yo:

pues quien vive más de una vida

más de una muerte ha de morir.

IV.

No se celebran oficios el día

en que se ahorca a un hombre:

el corazón del capellán está demasiado asqueado

o su rostro está demasiado lívido

o hay algo escrito en sus ojos

que nadie debe ver.

Así que nos tuvieron encerrados casi hasta mediodía

Y entonces sonó la campana

y l os guardias con sus tintineantes llaves abrieron todas las celdas a la espera

y bajamos pesadamente la escalera de hierro

cada uno desde su infierno particular.

Salimos al dulce aire de Dios,

Pero no como de costumbre,

pues el rostro de un hombre estaba blanco de miedo

y el de otro estaba gris

y nunca he visto a hombres tristes que miraran

con tanta avidez la luz del día.

Nunca vi a hombres tristes que miraran

con ojos tan ávidos

ese pequeño toldo azul

al que los presos llaman cielo,

y cada nube que pasaba

en tan extraña libertad.

Pero había entre nosotros algunos

que caminaban con la cabeza abatida

y sabían que, de haber tenido cada cual su merecido,

habrían tenido que morir en su lugar;

pues aquél sólo había matado algo vivo,

mientras que ellos habían matado a los muertos.

Pues quien peca por segunda vez

despierta al dolor a un alma muerta

y arranca de su sucio sudario

y la hace volver a sangrar,

¡y la hace sangrar goterones de sangre,

Y la hace sangrar en vano.

Cual monos o payasos, en ridículo atuendo

salpicados de flechas curvas,

dimos vueltas y vueltas en silencio

al resbaladizo patio asfaltado;

dimos vueltas y vueltas en silencio

y nadie dijo una palabra.

Dimos vueltas y vueltas en silencio

y por todos los cerebros en blanco

el recuerdo de cosas terribles

cruzó como un terrible viento,

y el horror caminaba airado ante cada hombre,

y el terror se arrastraba tras él.

Los guardias se pavoneaban arriba y abajo

y custodiaban su rebaño de bestias; sus uniformes estaban impecables

y vestían galas de domingo,

pero sabíamos el trabajo que habían hecho

por la cal viva de sus botas.

Pues donde se abría una ancha fosa,

no había ya fosa ninguna:

sólo un trecho de arena y barro

junto al horrible muro de la cárcel

y un montoncito de ardiente cal

para que aquel hombre tuviera su sudario.

Pues tiene un sudario, ese desdichado,

del que pocos hombres pueden alardear:

¡muy hondo bajo el patio de una cárcel,

desnudo para mayor afrenta,

yace, con grillos en los pies,

envuelto en una sábana de fuego!

Y todo el tiempo la ardiente cal

devora la carne y los huesos,

devora de noche el hueso quebradizo

y de día la tierna carne,

pero en todo momento devora el corazón.

Durante tres largos años no sembrarán

allí, ni plantarán;

durante tres largos años ese lugar maldito

seguirá estéril y desnudo

y contemplará el perplejo cielo

con irreprochable mirada.

Piensan que el corazón de un asesino pudriría

cualquier semilla que sembraran.

¡No es cierto! La buena tierra de Dios

es más bondadosa de los que creen los hombres

y la rosa roja florecería más roja,

y más blanca la rosa blanca

¡De su boca brotaría una rosa muy, muy roja!

¡De su corazón una rosa blanca!

Pues ¿quién puede decir de qué extraño modo

revela Cristo su voluntad,

si el seco cayado del peregrino

floreció a la vista del gran papa?

Mas ni la rosa blanca como la leche ni la roja

pueden florecer en el aire de la cárcel;

cascotes, guijarros y pedernales

es lo que nos dan allí:

pues ya se sabe que las flores curan

la desesperación del hombre común.

De modo que ni la rosa roja como el vino ni la blanca

caerán nunca pétalo a pétalo

sobre ese trecho de arena y barro que está

junto al horrible muro de la cárcel

para contarles a los hombres que andan por el patio

que el hijo de Dios murió por todos.

Pero aunque el horrible muro de la cárcel

lo rodea aún por todas partes

y aunque un espíritu no pueda vagar de noche

cuando está atado con grilletes

y aunque un espíritu sólo pueda llorar si yace en suelo tan limpio,

él está en paz – ese desdichado-,

en paz o pronto lo estará:

ya no hay nada que lo enfurezca,

ni pasará el terror al mediodía,

pues la oscura tierra en que yace

no tiene ni sol ni luna.

Lo ahorcaron como se ahorca a un animal:

no hubo siquiera un toque de campana,

un réquiem que habría podido llevar

consuelo a su alma asustada,

sino que se lo llevaron a toda prisa

y lo escondieron en un hoyo.

Los guardias lo despojaron de sus ropas

y lo entregaron a las moscas,

se burlaron de su garganta hinchada y cárdenas

y de sus ojos fijos y saltones,

y con grandes risotadas arrumbaron el sudario

en que yace el condenado.

El capellán no se arrodilló para rezar

en su deshonra tumba,

ni la señaló con la bendita cruz

que Cristo dio a los pecadores

-y aquel hombre era uno de aquellos

por cuya salvación bajó Cristo a la tierra.

Aunque todo está bien; solo ha traspasado

el límite prefijado de la vida

y ajenas lágrimas llenarán para él

la urna de la piedad, hace tiempo rota,

pues quienes le lloren serán los parias

y los parias siempre lloran.

V.

Yo no sé si las leyes son justas

o si las leyes son injustas;

todo lo que sabemos los que estamos en la cárcel

es que el muro es sólido

y que cada día es como un año,

un año días muy largos.

Pero sí sé esto: que toda la ley

que los hombres han hecho para el hombre,

desde que el primer hombre quitó la vida a su hermano

y dio comienzo este triste mundo,

no hace más que rechazar el grano y retener la paja

con su perverso cedazo.

También esto sé – y qué bueno sería

que todo el mundo lo supiera-:

que cada cárcel que el hombre construye está construida con ladrillos de infamia

y cercada con rejas para que Cristo no vea

cómo mutilan los hombres a sus hermanos.

Con rejas emborronan la amable luna

y ciegan el benéfico sol,

y hacen bien en ocultar su infierno,

¡porque en él se hacen cosas

que ni el hijo de Dios ni el hijo del hombre

deben ver jamás!

Las más viles acciones, cual yerbas venenosas,

florecen bien en el aire de la cárcel;

sólo lo que en el hombre hay de bueno

se agosta y marchita allí;

la pálida angustia guarda la pesada puerta y el carcelero es la desesperación.

Pues matan de hambre al chiquillo asustado

hasta que llora de noche y de día,

y azotan al débil y flagelan al tonto,

y se mofan del viejo y canoso,

y algunos enloquecen, y todos se vuelven peores,

y nadie puede decir ni una palabra.

Cada estrecha celda en que habitamos

es una infecta y oscura letrina,

y el fétido aliento de la muerte viviente

asfixia nuestras enrejadas mirillas

y todo, salvo la lujuria, es triturado hasta hacerlo polvo

en esta máquina de la humanidad.

El agua salobre que bebemos

brota con un limo nauseabundo,

el amargo pan que pesan en balanzas

está lleno de cal y yeso,

y el sueño no quiere acostarse, sino que camina

con sus ojos desorbitados y va dando las horas a gritos.

Pero aunque la flaca hambre y la fresca sed

luchan como el áspid con la víbora ,

poco nos preocupa el rancho de la cárcel,

pues lo que hiela y mata de golpe

es que cada piedra que levantamos de día

se convierte de noche en nuestro corazón.

Con la medianoche siempre en el corazón

y luz crepuscular en la celda

damos vueltas al manubrio o desgarramos sogas,

cada cual en su infierno particular,

y el silencio es mucho masa terrible

que el sonido de una campana hendida.

Y nunca se acerca una voz humana

a decir una palabra amable,

y el ojo que atisba a través de la puerta

es despiadado y duro,

y, olvidados por todos, nos pudrimos y pudrimos,

deshechos en cuerpo y alma.

Yasí herrumbramos la férrea cadena de la vida,

Envilecidos y solos;

y hay hombres que juran, y hay hombres que lloran,

y hay hombres que no emiten un gemido,

pero las leyes eternas de Dios son bondadosas

y parten el corazón de piedra.

Y cada corazón humano que se rompe

en una celda o en el patio de la cárcel

es como aquel cofre roto que dio su tesoro al Señor

y llenó la impura casa del leproso

con la esencia del más costoso nardo.

¡Ah, felices aquellos cuyos corazones pueden romperse

Y conquistar la paz del perdón!

¿De qué otra forma podría el hombre realizar su plan

y purificar su alma de pecado?

¿Cómo, sino a través de un corazón roto, puede entrar en ella Cristo nuestro Señor?

Y aquel de la garganta hinchada y cárdenas

y de los ojos fijos y saltones

aguarda las santas manos que condujeron

a un ladrón al paraíso;

y un corazón roto contrito

no lo desperdiciará el Señor.

El hombre de rojo que lee la ley

le dio tres semanas de vida,

tres cortas semanas en que curar

su alma de la lucha de su alma

y purificar de toda mancha de sangre

la mano que empuñó el cuchillo.

Y con lágrimas de sangre purificó se mano,

la mano que empuñó el acero,

pues sólo la sangre puede enjugar la sangre

y sólo las lágrimas pueden sanar,

y la mancha carmesí que fue de Caín

se transformó en el sello níveo de Cristo.

VI.

En la cárcel de Reading, junto a la ciudad de Reading,

hay una tumba infamante

y en ella yace un desdichado

devorado por dientes de fuego,

yace en un ardiente sudario

y su tumba no tiene nombre.

Y allí, hasta que Cristo llame a los muertos,

dejadle yacer en silencio;

no hay por qué derramar lágrimas necias ni exhalar sonoros suspiros:

aquel hombre había matado lo que amaba

y por eso tuvo que morir.

Y todos los hombres matan lo que aman,

que lo oiga todo el mundo,

unos lo hacen con una mirada amarga,

otros con una palabra zalamera;

el cobarde lo hace con un beso,

¡el valiente con una espada!

***

The Ballad of Reading Gaol

Oscar Wilde

In Memoriam

C.T.W.

Sometime Trooper of

The Royal Horse Guards.

Obiit H.M. Prison, Reading, Berkshire,

July 7th, 1896

I.

He did not wear his scarlet coat,

For blood and wine are red,

And blood and wine were on his hands

When they found him with the dead,

The poor dead woman whom he loved,

And murdered in her bed.

He walked amongst the Trial Men

In a suit of shabby grey;

A cricket cap was on his head,

And his step seemed light and gay;

But I never saw a man who looked

So wistfully at the day.

I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky,

And at every drifting cloud that went

With sails of silver by.

I walked, with other souls in pain,

Within another ring,

And was wondering if the man had done

A great or little thing,

When a voice behind me whispered low,

«That fellow’s got to swing.»

Dear Christ! the very prison walls

Suddenly seemed to reel,

And the sky above my head became

Like a casque of scorching steel;

And, though I was a soul in pain,

My pain I could not feel.

I only knew what hunted thought

Quickened his step, and why

He looked upon the garish day

With such a wistful eye;

The man had killed the thing he loved

And so he had to die.

Yet each man kills the thing he loves

By each let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

Some kill their love when they are young,

And some when they are old;

Some strangle with the hands of Lust,

Some with the hands of Gold:

The kindest use a knife, because

The dead so soon grow cold.

Some love too little, some too long,

Some sell, and others buy;

Some do the deed with many tears,

And some without a sigh:

For each man kills the thing he loves,

Yet each man does not die.

He does not die a death of shame

On a day of dark disgrace,

Nor have a noose about his neck,

Nor a cloth upon his face,

Nor drop feet foremost through the floor

Into an empty place

He does not sit with silent men

Who watch him night and day;

Who watch him when he tries to weep,

And when he tries to pray;

Who watch him lest himself should rob

The prison of its prey.

He does not wake at dawn to see

Dread figures throng his room,

The shivering Chaplain robed in white,

The Sheriff stern with gloom,

And the Governor all in shiny black,

With the yellow face of Doom.

He does not rise in piteous haste

To put on convict-clothes,

While some coarse-mouthed Doctor gloats, and notes

Each new and nerve-twitched pose,

Fingering a watch whose little ticks

Are like horrible hammer-blows.

He does not know that sickening thirst

That sands one’s throat, before

The hangman with his gardener’s gloves

Slips through the padded door,

And binds one with three leathern thongs,

That the throat may thirst no more.

He does not bend his head to hear

The Burial Office read,

Nor, while the terror of his soul

Tells him he is not dead,

Cross his own coffin, as he moves

Into the hideous shed.

He does not stare upon the air

Through a little roof of glass;

He does not pray with lips of clay

For his agony to pass;

Nor feel upon his shuddering cheek

The kiss of Caiaphas.

II.

Six weeks our guardsman walked the yard,

In a suit of shabby grey:

His cricket cap was on his head,

And his step seemed light and gay,

But I never saw a man who looked

So wistfully at the day.

I never saw a man who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

Which prisoners call the sky,

And at every wandering cloud that trailed

Its ravelled fleeces by.

He did not wring his hands, as do

Those witless men who dare

To try to rear the changeling Hope

In the cave of black Despair:

He only looked upon the sun,

And drank the morning air.

He did not wring his hands nor weep,

Nor did he peek or pine,

But he drank the air as though it held

Some healthful anodyne;

With open mouth he drank the sun

As though it had been wine!

And I and all the souls in pain,

Who tramped the other ring,

Forgot if we ourselves had done

A great or little thing,

And watched with gaze of dull amaze

The man who had to swing.

And strange it was to see him pass

With a step so light and gay,

And strange it was to see him look

So wistfully at the day,

And strange it was to think that he

Had such a debt to pay.

For oak and elm have pleasant leaves

That in the spring-time shoot:

But grim to see is the gallows-tree,

With its adder-bitten root,

And, green or dry, a man must die

Before it bears its fruit!

The loftiest place is that seat of grace

For which all worldlings try:

But who would stand in hempen band

Upon a scaffold high,

And through a murderer’s collar take

His last look at the sky?

It is sweet to dance to violins

When Love and Life are fair:

To dance to flutes, to dance to lutes

Is delicate and rare:

But it is not sweet with nimble feet

To dance upon the air!

So with curious eyes and sick surmise

We watched him day by day,

And wondered if each one of us

Would end the self-same way,

For none can tell to what red Hell

His sightless soul may stray.

At last the dead man walked no more

Amongst the Trial Men,

And I knew that he was standing up

In the black dock’s dreadful pen,

And that never would I see his face

In God’s sweet world again.

Like two doomed ships that pass in storm

We had crossed each other’s way:

But we made no sign, we said no word,

We had no word to say;

For we did not meet in the holy night,

But in the shameful day.

A prison wall was round us both,

Two outcast men were we:

The world had thrust us from its heart,

And God from out His care:

And the iron gin that waits for Sin

Had caught us in its snare.

III.

In Debtors’ Yard the stones are hard,

And the dripping wall is high,

So it was there he took the air

Beneath the leaden sky,

And by each side a Warder walked,

For fear the man might die.

Or else he sat with those who watched

His anguish night and day;

Who watched him when he rose to weep,

And when he crouched to pray;

Who watched him lest himself should rob

Their scaffold of its prey.

The Governor was strong upon

The Regulations Act:

The Doctor said that Death was but

A scientific fact:

And twice a day the Chaplain called

And left a little tract.

And twice a day he smoked his pipe,

And drank his quart of beer:

His soul was resolute, and held

No hiding-place for fear;

He often said that he was glad

The hangman’s hands were near.

But why he said so strange a thing

No Warder dared to ask:

For he to whom a watcher’s doom

Is given as his task,

Must set a lock upon his lips,

And make his face a mask.

Or else he might be moved, and try

To comfort or console:

And what should Human Pity do

Pent up in Murderers’ Hole?

What word of grace in such a place

Could help a brother’s soul?

With slouch and swing around the ring

We trod the Fool’s Parade!

We did not care: we knew we were

The Devil’s Own Brigade:

And shaven head and feet of lead

Make a merry masquerade.

We tore the tarry rope to shreds

With blunt and bleeding nails;

We rubbed the doors, and scrubbed the floors,

And cleaned the shining rails:

And, rank by rank, we soaped the plank,

And clattered with the pails.

We sewed the sacks, we broke the stones,

We turned the dusty drill:

We banged the tins, and bawled the hymns,

And sweated on the mill:

But in the heart of every man

Terror was lying still.

So still it lay that every day

Crawled like a weed-clogged wave:

And we forgot the bitter lot

That waits for fool and knave,

Till once, as we tramped in from work,

We passed an open grave.

With yawning mouth the yellow hole

Gaped for a living thing;

The very mud cried out for blood

To the thirsty asphalte ring:

And we knew that ere one dawn grew fair

Some prisoner had to swing.

Right in we went, with soul intent

On Death and Dread and Doom:

The hangman, with his little bag,

Went shuffling through the gloom

And each man trembled as he crept

Into his numbered tomb.

That night the empty corridors

Were full of forms of Fear,

And up and down the iron town

Stole feet we could not hear,

And through the bars that hide the stars

White faces seemed to peer.

He lay as one who lies and dreams

In a pleasant meadow-land,

The watcher watched him as he slept,

And could not understand

How one could sleep so sweet a sleep

With a hangman close at hand?

But there is no sleep when men must weep

Who never yet have wept:

So we–the fool, the fraud, the knave–

That endless vigil kept,

And through each brain on hands of pain

Another’s terror crept.

Alas! it is a fearful thing

To feel another’s guilt!

For, right within, the sword of Sin

Pierced to its poisoned hilt,

And as molten lead were the tears we shed

For the blood we had not spilt.

The Warders with their shoes of felt

Crept by each padlocked door,

And peeped and saw, with eyes of awe,

Grey figures on the floor,

And wondered why men knelt to pray

Who never prayed before.

All through the night we knelt and prayed,

Mad mourners of a corpse!

The troubled plumes of midnight were

The plumes upon a hearse:

And bitter wine upon a sponge

Was the savour of Remorse.

The cock crew, the red cock crew,

But never came the day:

And crooked shape of Terror crouched,

In the corners where we lay:

And each evil sprite that walks by night

Before us seemed to play.

They glided past, they glided fast,

Like travellers through a mist:

They mocked the moon in a rigadoon

Of delicate turn and twist,

And with formal pace and loathsome grace

The phantoms kept their tryst.

With mop and mow, we saw them go,

Slim shadows hand in hand:

About, about, in ghostly rout

They trod a saraband:

And the damned grotesques made arabesques,

Like the wind upon the sand!

With the pirouettes of marionettes,

They tripped on pointed tread:

But with flutes of Fear they filled the ear,

As their grisly masque they led,

And loud they sang, and loud they sang,

For they sang to wake the dead.

«Oho!» they cried, «The world is wide,

But fettered limbs go lame!

And once, or twice, to throw the dice

Is a gentlemanly game,

But he does not win who plays with Sin

In the secret House of Shame.»

No things of air these antics were

That frolicked with such glee:

To men whose lives were held in gyves,

And whose feet might not go free,

Ah! wounds of Christ! they were living things,

Most terrible to see.

Around, around, they waltzed and wound;

Some wheeled in smirking pairs:

With the mincing step of demirep

Some sidled up the stairs:

And with subtle sneer, and fawning leer,

Each helped us at our prayers.

The morning wind began to moan,

But still the night went on:

Through its giant loom the web of gloom

Crept till each thread was spun:

And, as we prayed, we grew afraid

Of the Justice of the Sun.

The moaning wind went wandering round

The weeping prison-wall:

Till like a wheel of turning-steel

We felt the minutes crawl:

O moaning wind! what had we done

To have such a seneschal?

At last I saw the shadowed bars

Like a lattice wrought in lead,

Move right across the whitewashed wall

That faced my three-plank bed,

And I knew that somewhere in the world

God’s dreadful dawn was red.

At six o’clock we cleaned our cells,

At seven all was still,

But the sough and swing of a mighty wing

The prison seemed to fill,

For the Lord of Death with icy breath

Had entered in to kill.

He did not pass in purple pomp,

Nor ride a moon-white steed.

Three yards of cord and a sliding board

Are all the gallows’ need:

So with rope of shame the Herald came

To do the secret deed.

We were as men who through a fen

Of filthy darkness grope:

We did not dare to breathe a prayer,

Or give our anguish scope:

Something was dead in each of us,

And what was dead was Hope.

For Man’s grim Justice goes its way,

And will not swerve aside:

It slays the weak, it slays the strong,

It has a deadly stride:

With iron heel it slays the strong,

The monstrous parricide!

We waited for the stroke of eight:

Each tongue was thick with thirst:

For the stroke of eight is the stroke of Fate

That makes a man accursed,

And Fate will use a running noose

For the best man and the worst.

We had no other thing to do,

Save to wait for the sign to come:

So, like things of stone in a valley lone,

Quiet we sat and dumb:

But each man’s heart beat thick and quick

Like a madman on a drum!

With sudden shock the prison-clock

Smote on the shivering air,

And from all the gaol rose up a wail

Of impotent despair,

Like the sound that frightened marshes hear

From a leper in his lair.

And as one sees most fearful things

In the crystal of a dream,

We saw the greasy hempen rope

Hooked to the blackened beam,

And heard the prayer the hangman’s snare

Strangled into a scream.

And all the woe that moved him so

That he gave that bitter cry,

And the wild regrets, and the bloody sweats,

None knew so well as I:

For he who live more lives than one

More deaths than one must die.

IV.

There is no chapel on the day

On which they hang a man:

The Chaplain’s heart is far too sick,

Or his face is far to wan,

Or there is that written in his eyes

Which none should look upon.

So they kept us close till nigh on noon,

And then they rang the bell,

And the Warders with their jingling keys

Opened each listening cell,

And down the iron stair we tramped,

Each from his separate Hell.

Out into God’s sweet air we went,

But not in wonted way,

For this man’s face was white with fear,

And that man’s face was grey,

And I never saw sad men who looked

So wistfully at the day.

I never saw sad men who looked

With such a wistful eye

Upon that little tent of blue

We prisoners called the sky,

And at every careless cloud that passed

In happy freedom by.

But their were those amongst us all

Who walked with downcast head,

And knew that, had each go his due,

They should have died instead:

He had but killed a thing that lived

Whilst they had killed the dead.

For he who sins a second time

Wakes a dead soul to pain,

And draws it from its spotted shroud,

And makes it bleed again,

And makes it bleed great gouts of blood

And makes it bleed in vain!

Like ape or clown, in monstrous garb

With crooked arrows starred,

Silently we went round and round

The slippery asphalte yard;

Silently we went round and round,

And no man spoke a word.

Silently we went round and round,

And through each hollow mind

The memory of dreadful things

Rushed like a dreadful wind,

An Horror stalked before each man,

And terror crept behind.

The Warders strutted up and down,

And kept their herd of brutes,

Their uniforms were spick and span,

And they wore their Sunday suits,

But we knew the work they had been at

By the quicklime on their boots.

For where a grave had opened wide,

There was no grave at all:

Only a stretch of mud and sand

By the hideous prison-wall,

And a little heap of burning lime,

That the man should have his pall.

For he has a pall, this wretched man,

Such as few men can claim:

Deep down below a prison-yard,

Naked for greater shame,

He lies, with fetters on each foot,

Wrapt in a sheet of flame!

And all the while the burning lime

Eats flesh and bone away,

It eats the brittle bone by night,

And the soft flesh by the day,

It eats the flesh and bones by turns,

But it eats the heart alway.

For three long years they will not sow

Or root or seedling there:

For three long years the unblessed spot

Will sterile be and bare,

And look upon the wondering sky

With unreproachful stare.

They think a murderer’s heart would taint

Each simple seed they sow.

It is not true! God’s kindly earth

Is kindlier than men know,

And the red rose would but blow more red,

The white rose whiter blow.

Out of his mouth a red, red rose!

Out of his heart a white!

For who can say by what strange way,

Christ brings his will to light,

Since the barren staff the pilgrim bore

Bloomed in the great Pope’s sight?

But neither milk-white rose nor red

May bloom in prison air;

The shard, the pebble, and the flint,

Are what they give us there:

For flowers have been known to heal

A common man’s despair.

So never will wine-red rose or white,

Petal by petal, fall

On that stretch of mud and sand that lies

By the hideous prison-wall,

To tell the men who tramp the yard

That God’s Son died for all.

Yet though the hideous prison-wall

Still hems him round and round,

And a spirit man not walk by night

That is with fetters bound,

And a spirit may not weep that lies

In such unholy ground,

He is at peace–this wretched man–

At peace, or will be soon:

There is no thing to make him mad,

Nor does Terror walk at noon,

For the lampless Earth in which he lies

Has neither Sun nor Moon.

They hanged him as a beast is hanged:

They did not even toll

A requiem that might have brought

Rest to his startled soul,

But hurriedly they took him out,

And hid him in a hole.

They stripped him of his canvas clothes,

And gave him to the flies;

They mocked the swollen purple throat

And the stark and staring eyes:

And with laughter loud they heaped the shroud

In which their convict lies.

The Chaplain would not kneel to pray

By his dishonoured grave:

Nor mark it with that blessed Cross

That Christ for sinners gave,

Because the man was one of those

Whom Christ came down to save.

Yet all is well; he has but passed

To Life’s appointed bourne:

And alien tears will fill for him

Pity’s long-broken urn,

For his mourner will be outcast men,

And outcasts always mourn.

V.

I know not whether Laws be right,

Or whether Laws be wrong;

All that we know who lie in goal

Is that the wall is strong;

And that each day is like a year,

A year whose days are long.

But this I know, that every Law

That men have made for Man,

Since first Man took his brother’s life,

And the sad world began,

But straws the wheat and saves the chaff

With a most evil fan.

This too I know–and wise it were

If each could know the same–

That every prison that men build

Is built with bricks of shame,

And bound with bars lest Christ should see

How men their brothers maim.

With bars they blur the gracious moon,

And blind the goodly sun:

And they do well to hide their Hell,

For in it things are done

That Son of God nor son of Man

Ever should look upon!

The vilest deeds like poison weeds

Bloom well in prison-air:

It is only what is good in Man

That wastes and withers there:

Pale Anguish keeps the heavy gate,

And the Warder is Despair

For they starve the little frightened child

Till it weeps both night and day:

And they scourge the weak, and flog the fool,

And gibe the old and grey,

And some grow mad, and all grow bad,

And none a word may say.

Each narrow cell in which we dwell

Is foul and dark latrine,

And the fetid breath of living Death

Chokes up each grated screen,

And all, but Lust, is turned to dust

In Humanity’s machine.

The brackish water that we drink

Creeps with a loathsome slime,

And the bitter bread they weigh in scales

Is full of chalk and lime,

And Sleep will not lie down, but walks

Wild-eyed and cries to Time.

But though lean Hunger and green Thirst

Like asp with adder fight,

We have little care of prison fare,

For what chills and kills outright

Is that every stone one lifts by day

Becomes one’s heart by night.

With midnight always in one’s heart,

And twilight in one’s cell,

We turn the crank, or tear the rope,

Each in his separate Hell,

And the silence is more awful far

Than the sound of a brazen bell.

And never a human voice comes near

To speak a gentle word:

And the eye that watches through the door

Is pitiless and hard:

And by all forgot, we rot and rot,

With soul and body marred.

And thus we rust Life’s iron chain

Degraded and alone:

And some men curse, and some men weep,

And some men make no moan:

But God’s eternal Laws are kind

And break the heart of stone.

And every human heart that breaks,

In prison-cell or yard,

Is as that broken box that gave

Its treasure to the Lord,

And filled the unclean leper’s house

With the scent of costliest nard.

Ah! happy day they whose hearts can break

And peace of pardon win!

How else may man make straight his plan

And cleanse his soul from Sin?

How else but through a broken heart

May Lord Christ enter in?

And he of the swollen purple throat.

And the stark and staring eyes,

Waits for the holy hands that took

The Thief to Paradise;

And a broken and a contrite heart

The Lord will not despise.

The man in red who reads the Law

Gave him three weeks of life,

Three little weeks in which to heal

His soul of his soul’s strife,

And cleanse from every blot of blood

The hand that held the knife.

And with tears of blood he cleansed the hand,

The hand that held the steel:

For only blood can wipe out blood,

And only tears can heal:

And the crimson stain that was of Cain

Became Christ’s snow-white seal.

VI.

In Reading gaol by Reading town

There is a pit of shame,

And in it lies a wretched man

Eaten by teeth of flame,

In burning winding-sheet he lies,

And his grave has got no name.

And there, till Christ call forth the dead,

In silence let him lie:

No need to waste the foolish tear,

Or heave the windy sigh:

The man had killed the thing he loved,

And so he had to die.

And all men kill the thing they love,

By all let this be heard,

Some do it with a bitter look,

Some with a flattering word,

The coward does it with a kiss,

The brave man with a sword!

***

Encontré esta: https://grupoigneo.com/blog/entrevista-jose-baroja-literatura/